Air Masses: The Gathering Armies #

Before any battle begins, the armies must gather. In the world of meteorology, these armies are called Air Masses.

Imagine a vast body of air sitting over a huge, uniform surface—like the frozen plains of Siberia or the warm waters of the tropical Pacific—for a long time. Slowly, the air adopts the “culture” of that land. If the land is cold and dry, the air becomes cold and dry. This process creates a distinct identity for the air.

The Definition: An air mass is a large body of air having little horizontal variation in temperature and moisture, extending from the surface to the lower stratosphere.

The Training Grounds (Source Regions): For an army to form, it needs a stable training ground. These are called Source Regions. The ideal training grounds are areas with high pressure and gentle, divergent air circulation (anticyclones), where air stays still long enough to acquire properties. (Note: There are no major source regions in the mid-latitudes because that is the battlefield where the armies fight (cyclones), so the air never sits still.)

The Five Regiments: Based on their “training,” we classify them into five distinct types:

- Maritime Tropical (mT): Born over warm tropical oceans (like the Gulf of Mexico). They are warm, humid, and unstable.

- Continental Tropical (cT): Born over hot deserts (Sahara, Australia). They are dry, hot, and stable.

- Maritime Polar (mP): Born over high-latitude oceans (40∘–60∘). They are cool and moist.

- Continental Polar (cP): Born over snow-covered continents (Northern Canada, Siberia). They are dry, cold, and stable.

- Continental Arctic (cA): The elite cold guard from the permanent ice caps of Antarctica and the Arctic.

Fronts: The Clash of Clans #

When two different armies (Air Masses) meet, they do not mix easily. They have different densities and temperatures. Instead, they crash into each other. The boundary zone between these warring armies is called a Front.

- Frontogenesis: The start of the war (formation of the front).

- Frontolysis: The end of the war (dissipation of the front).

The Three Battle Scenarios:

1. Cold Front:

- The Scenario: The Cold Air Mass (cP) is the aggressor. It marches forward, shoving the lighter Warm Air Mass (mT) violently upward.

- The Action: Because the cold air acts like a steep wedge/bulldozer, the warm air rises rapidly.

- The Visuals: This rapid uplift creates towering Cumulonimbus clouds (thunderclouds).

- The Weather: Intense, short-duration heavy rainfall, thunderstorms, and sometimes tornadoes occur in the warm sector. The temperature drops sharply (up to 15 degrees within an hour) as the front passes.

2. Warm Front:

- The Scenario: The Warm Air Mass is advancing, but it is not strong enough to push the heavy cold air out of the way.

- The Action: Instead of bulldozing, the warm air gently climbs over the back of the retreating cold air.

- The Visuals: The slope is gentle. You see a specific hierarchy of clouds: first high Cirrus, then Cirrostratus (creating a halo around the sun), Altostratus, and finally Nimbostratus.

- The Weather: It brings moderate, gentle precipitation that lasts for hours or days over a large area.

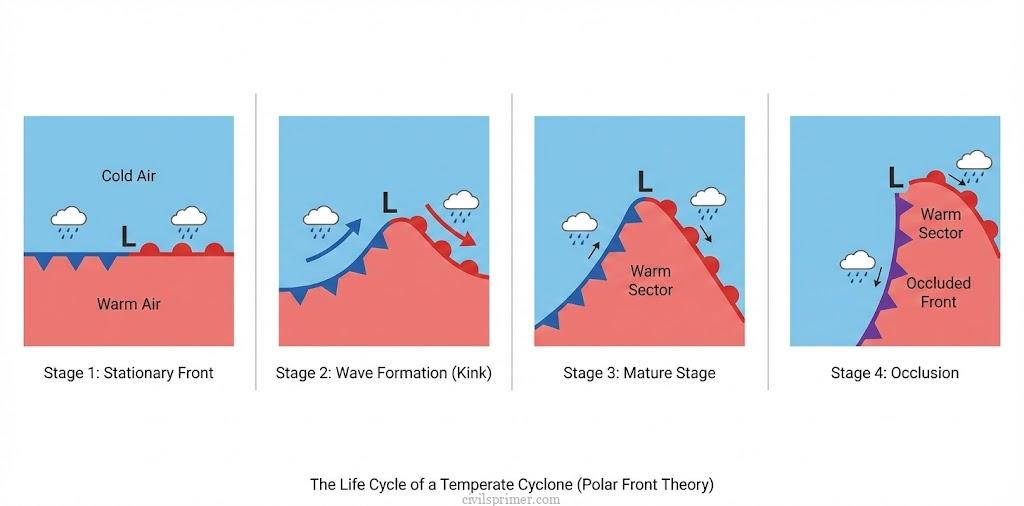

3. Stationary Front:

- The Scenario: Neither side can win. The surface position of the front does not move. Winds blow parallel to the front.

- The Weather: It creates Cumulonimbus clouds and flooding rain if it stays for too long.

4. Occluded Front:

- The Scenario: A Cold Front moves faster than a Warm Front. Eventually, the cold front catches up, lifting the warm air entirely off the ground.

- The Result: The warm air is trapped above, isolated from the surface. This marks the end of the cyclone’s life cycle.

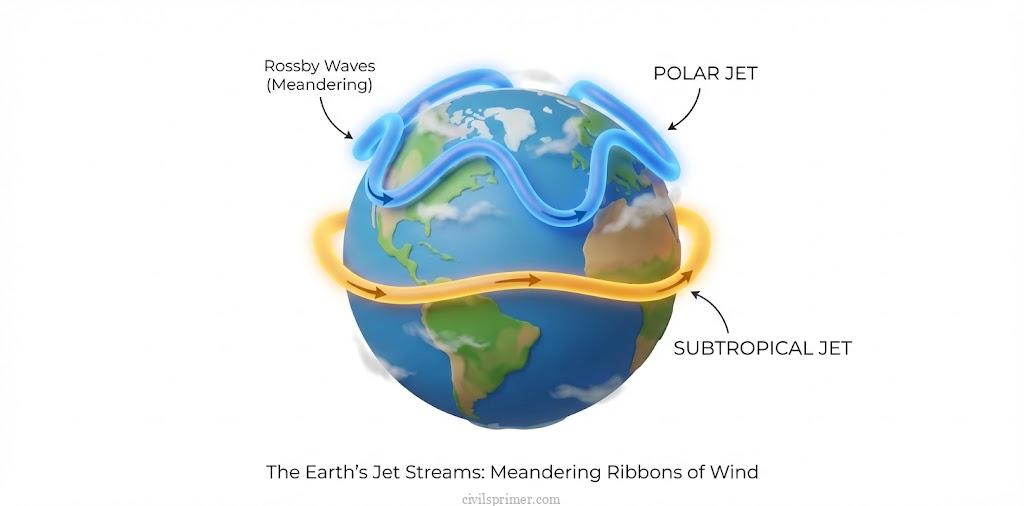

Jet Streams: The Commanders in the Sky #

High above these surface battles, in the upper troposphere (9–12 km altitude), flow narrow, meandering rivers of fast-moving winds called Jet Streams. They are the puppeteers controlling the weather systems below.

Profile of the Commander:

- What are they? Narrow bands of strong westerly winds (flowing West → East) located near the Tropopause.

- Why do they exist? They form due to the sharp pressure difference between air masses (e.g., between cold polar air and warm temperate air) and the Coriolis Force.

- Speed: They can reach speeds up to 400 kmph, averaging 120 kmph in winter.

The Two Generals:

- Polar Jet Stream: Flows between the Polar and Temperate air masses (approx 60∘ latitude). It is stronger and lower (6–9 km altitude) because the temperature contrast is sharper there.

- Subtropical Jet Stream (STJ): Flows above the subtropical high-pressure belt (30∘ latitude). It is higher (10–16 km altitude).

The Strategy (Rossby Waves): These rivers don’t flow straight; they wiggle like a snake. These Meanders are called Rossby Waves.

- Ridges: The parts of the wave bulging towards the poles (High Pressure).

- Troughs: The parts bulging towards the Equator (Low Pressure).

- The Impact: The divergence and convergence of air in these waves suck air up from the ground (creating cyclones) or push air down (creating anticyclones). Thus, Jet Streams “steer” the cyclones.

A Special Guest: The Tropical Easterly Jet (TEJ) Unlike the permanent Westerlies, a temporary jet forms over India during summer. It flows East to West.

- Origin: The intense heating of the Tibetan Plateau.

- Mission: It helps kick-start the Indian Southwest Monsoon by intensifying the high pressure over the Indian Ocean (Mascarene High).

Temperate Cyclones: The Strategic War #

In the mid-latitudes (35–65 degrees), the “General from the North” (Polar air) meets the “General from the South” (Tropical air). Their collision creates the Temperate Cyclone (also called Extra-Tropical or Frontal Cyclone). These storms are born from Frontogenesis—the dynamic clash of air masses.

- The Setup: A stationary front forms between the cold polar air and warm westerly air (Polar Front Theory).

- The Twist: A disturbance (often caused by the Jet Stream above) kinks the front. The warm air pushes north, and cold air pushes south, creating a counter-clockwise spin (in the Northern Hemisphere).

- The Shape: They are asymmetrical and look like an inverted ‘V’ covering a massive area (up to 2000 km in diameter).

- The Movement: They travel West to East, driven by the Westerlies.

- The Weather: They bring gradual, long-lasting precipitation. In winter, they bring the “Western Disturbances” to India, causing snow in the Himalayas and rain in the plains, crucial for the Rabi crops.

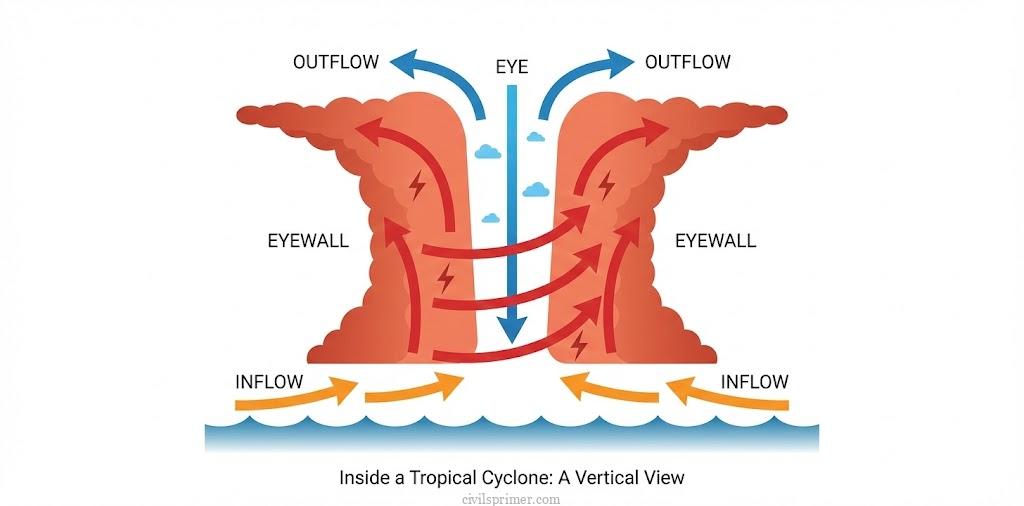

Tropical Cyclones: The Heat Monster #

While Temperate Cyclones are strategic wars along a front, Tropical Cyclones are violent, thermal engines. They are not born from fronts; they are born from Heat. To bake a tropical cyclone, nature needs specific ingredients:

- Warm Sea: Surface temperature >27∘C extending to 60m depth. This provides the moisture and Latent Heat of Condensation (the fuel).

- Coriolis Force: To spin the air. (This is why cyclones never form at the Equator where Coriolis is zero).

- Low Wind Shear: If winds at different heights blow at different speeds, they decapitate the storm. The winds must be uniform.

- Pre-existing Low: A weak disturbance to start the cycle.

The Anatomy of the Beast:

- The Eye: The center is a bizarre place. It is calm, with clear skies and sinking air. It is the area of lowest pressure.

- The Eyewall: Surrounding the eye is the most violent ring. Here, air spirals upward rapidly, creating the strongest winds and torrential rains. This is where the “Cumulonimbus” clouds tower highest.

- Spiral Bands: Bands of rain clouds spiral inward, feeding the beast.

Movement and Death: These storms move East to West (driven by Trade Winds) but curve Northwards. When they hit land (“Landfall”), their fuel line (moisture) is cut. Deprived of Latent Heat, they starve and die.

Bomb Cyclones A “Bomb Cyclone” is a mid-latitude cyclone that intensifies incredibly fast (pressure drops 24 mb in 24 hours). It happens when a cold air mass collides with a warm air mass, creating blizzard conditions.

The Comparison: Tropical vs. Temperate Cyclone #

| Feature | Tropical Cyclone | Temperate Cyclone |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Thermal (Latent Heat) | Dynamic (Fronts/Coriolis) |

| Latitude | 10∘−30∘ N/S | 35∘−65∘ N/S |

| Size | Small (<500 km) | Large (>1000 km) |

| Shape | Circular / Elliptical with Eye | Inverted ‘V’, No Eye |

| Direction | East → West | West → East |

| Rainfall | Heavy, short duration | Moderate, long duration |

| Fronts | Absent | Essential (Frontogenesis) |

UPSC Mains Subjective Previous Years Questions #

- Explain the relationship between air masses and local winds. (2025)

- Formation of temperate cyclone depends on the condition of axis of dilation. Elucidate. (2024)

- With suitable examples describe the impacts of the movement of air masses on weather and winds in different parts of the continents. (2022)

- What are the important factors responsible for Airmass modifications? (2021)

- Discuss the concept of air mass and explain its role in macro-climatic changes. (2016)

- Discuss as to how frontogenesis contributes to weather instability. (2015)

Related Latest Current Affairs #

- November, 2025: Rare Fujiwhara Effect in Bay of Bengal Global forecast models indicated a possible Fujiwhara interaction between two potential cyclonic storms forming in the Bay of Bengal. This rare phenomenon occurs when two nearby cyclonic vortices rotate around a common center due to the interaction of their wind circulations, potentially leading to a merger or altered storm tracks.

- November, 2025: Formation of Cyclone Ditwah and Cyclone Senyar Cyclone Ditwah formed over the southwest Bay of Bengal, while Cyclone Senyar developed in the Strait of Malacca/Andaman Sea. These systems highlight the active cyclogenesis during the retreating southwest monsoon season, driven by warm Sea Surface Temperatures (>28°C) and the southward shift of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).

- October, 2025: Cyclone Montha and Cyclone Shakhti The IMD tracked Cyclone Montha (Bay of Bengal) and Cyclone Shakhti (Arabian Sea). These tropical cyclones formed due to low-pressure centers over warm waters, where rising moist air releases Latent Heat; Cyclone Shakhti highlights the increasing trend of cyclogenesis in the Arabian Sea due to rising sea surface temperatures.

- October, 2025: Super Typhoon Ragasa Super Typhoon Ragasa, equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane with winds up to 250 km/h, impacted the Philippines and Southern China. Formed over the western Pacific Ocean due to warm waters and low wind shear, it serves as a prime example of intense tropical cyclone development.

- October, 2025: Severe Blizzard in Tibet A severe blizzard struck the eastern face of Mount Everest, trapping trekkers. This mid-latitude snowstorm forms when cold polar/continental air masses interact with moist maritime/tropical air, causing frontal or orographic uplift and intense precipitation accompanied by strong winds.

- August, 2025: Typhoon Kajiki Typhoon Kajiki, a powerful tropical cyclone, formed in the West Pacific and approached Vietnam with winds up to 166 km/h. It exemplifies a rotating low-pressure storm powered by Latent Heat from warm seawater, distinct from frontal-based temperate cyclones.

- January, 2025: Storm Eowyn (Bomb Cyclone) Storm Eowyn, a Bomb Cyclone, struck the British Isles. It formed due to “explosive cyclogenesis” (rapid pressure drop of ≥24 millibars in 24 hours) driven by a strong Jet Stream over the North Atlantic and the clash between cold Arctic air and warm ocean air.